In Wes Anderson’s Rushmore (still his masterpiece, in my humble opinion, though I retain a soft spot for Bottle Rocket, which I wrote about almost exactly ten years ago), hangdog extraordinaire Herman Blume (still Bill Murray’s best role, in my not-so-humble opinion)—long past lamenting what he’s gotten himself into, teaming up with exasperating wunderkind Max Fischer (still Jason Schwartzman’s best work, which no one can dispute)—assesses their latest scheme with resigned disbelief. “I spent eight million dollars on this,” he says. And Max, illustrating why, for all his foibles, his irrepressible (even delusional) optimism is the queer key to his success, asks, “And is that all you’re willing to spend?”

What does this have to do with writing? Well, not much. Except, you know, everything.

The money, of course, is a metaphor, at least as it applies to writers.

I thought of this epic scene while reading Emily Winter’s wonderful piece in the New York Times “I Got Rejected 101 Times.”

Only 101 times? I thought, sardonically, but in solidarity. And is that all you’re willing to endure?

When it comes to the long game of serious and sustained writing, virtually every essay I’ve ever read by any celebrated author mentions persistence. Talent, yes; hard work, obviously. But the word that comes up over and over is persistence. (More on that, here.) Famous authors frequently talk about peers or students who possess unbelievable ability, but give up, get complacent, can’t handle the rejection. And the proverbial bell tolls for any writer, at any level, who doesn’t merely understand, but embrace the reality of rejection being the one unalterable thing.

To her considerable credit, the point of Winter’s piece is acknowledging not only that rejection is inevitable, but—if accepted and processed with a positive attitude—at times useful. For one thing, it thickens the skin. For another, it’s imperative to keep from doing nothing; even the most haphazard schemes and dreams (once again invoking our friend Max Fischer) are antidotes to apathy. And, as any worthwhile writer understands, it’s not uncommon for initial failure to lead to opportunity, revision, improvement. Et cetera.

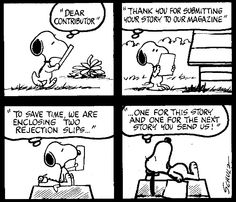

Needless to say, I know of what I speak. Oh, I know. I’ve experienced enough rejection that I can actually look back, with nostalgia, at the years when I saved each rejection slip (these were the not-so-great-old-days when writers printed poems and stories, put them in a large envelope with obligatory SASE, drove to the post office, paid to have them mailed to the desired literary magazine, and then waited weeks, or much more often, months, for that SASE to come back…rinse, wash, repeat), so that I might savor them once I eventually, inevitably, became a best-selling author. This was a practice I eventually discontinued, if for no other reason than to avoid being the first hoarder whose house became uninhabitable due to a pitiful topiary of rejection slips.

In 2015, I had the opportunity to write in some detail about a particularly memorable rejection, courtesy of The Quivering Pen, a fantastic site for writers (and readers) curated by David Abrams (himself an excellent reader and writer: check him out, here). That piece, entitled “My First Time,” is revisited below. I’d love to hear from you and your experience with rejection, especially how you’ve used it as motivation. Drop a line or leave a comment!

Let’s talk about the first.

There’s the first story I wrote. (Original story: fifth grade; vaguely plagiarized ones where, looking back and with apologies to Edgar Allan Poe, imitation was the sincerest form of flattery: third and fourth grades.)

There’s the first “adult” book I read. (Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, fourth grade. Huge mistake. Having seen the movies and read some comic book treatments, I thought I was ready for the real thing. It took me more than halfway through to understand Frankenstein was not, in fact, the monster.)

There’s the first success. (Being asked to compose and recite an original poem for an eighth-grade student assembly.)

There’s the first readership. (A series of features I wrote for my high school newspaper. For a teenager, a printed byline is as close to the big-time as it got, at least in the old-school era before social media and blogs.)

There’s the first publication. (A poem in my college literary magazine.)

There’s the first “important” publication. (A short story in another, better-known literary magazine.)

There’s the first in a series of unfortunate events. (Also known as writing workshops, wherein the cocky writer’s work gets, well, workshopped. Hilarity does not often ensue.)

There’s the first in a longer series of ceaseless rejection. (No comment necessary.)

There’s the first short story I knew would make me famous. (It’s still unpublished.)

There’s the first attempt at a novel. (Also unpublished. Fortunately, for all involved.)

There’s the subsequent, earnest attempt at a first novel. (Still a work-in-progress. Sort of.)

Nothing especially unique or noteworthy, right? All of these events or experiences were stepping stones most, if not all, writers will recognize and relate to. There is an evolution comprised of myriad firsts (and lasts), but what separates all but the most successful and/or lucky authors is what happens after the familiar epiphanies of the apprentice have occurred and it gets to the eventual, inevitable matter of perseverance.

The “first” that was, if not unique, for me the most formative and indelible, involved rejection and resolve.

Let me tell you a story: a famous writer saw a first chapter of this aforementioned novel. Famous writer picks up phone (people still used phones in those days) and tells unknown writer that he loves the material and wants his agent to look at it. Agent receives chapter, loves it too, and asks to see entire manuscript on an exclusive basis. Unknown writer thinks: this is it, the big break, the moment of truth, and other clichés. An entire summer passes, which is unfortunate. It happens to be the same summer unknown writer’s mother—who has been battling cancer for five years—begins to lose her final battle. By the time unknown writer’s mother passes away, the novel, the agent and the famous writer are about the farthest things from his mind. On the day of mother’s funeral, unknown writer makes the ill-advised decision to check his email before leaving the house. He sees the overdue email from agent. Something tells him not to open it, but of course he has to; according to logic and everything right in the world, not to mention the imperative of Cliché, this is the perfect time to see he’s about to be represented and eventually published, and this is the miracle he’ll employ to overcome his grief, and he’ll dedicate this book to his mother, without whom he could never have written it, or written anything.

Naturally, the email is, in fact, a rather terse (but apologetic) rejection.

And this unknown writer, in spite of himself, looks past the computer, looks beyond his disbelief, and looks out to whomever or whatever may be listening (or orchestrating this test of faith) and can’t quite believe hearing the words, in a voice that sounds a lot like his: “Is that all you got?”

No, this is not going to be the final, unkindest cut, the sign that failure is inevitable, the signal that it’s better to move on to other things, the message that it’s not meant to be. I’m not doing this, he thinks, because I want to, or that I hope to prove anything, or become famous (he has put away childish things). I’m doing this, he knows, because he doesn’t know what else he could possibly do with himself. He does it, he finally understands, because there’s nothing else he could imagine himself doing. And that the only failure is to stop. To be afraid, to give up.

It wasn’t the first rejection, obviously, and while it may be the biggest, it wasn’t the last. In addition to death and taxes, writers recognize at some point, however resignedly, that rejection will always be on offer, for free, forever.

And ultimately it mattered only in the sense that it didn’t matter. Or, it mattered a great deal in the sense that it was not enough to dissuade or discourage him from stumbling down a path he made up as he went along; that revealed itself only when he looked back on another piece of writing and thought: Good thing I didn’t stop.

This was the most important first, the first day of the rest of my life.