Destinee Harper

Found Between Pages: Volunteering with the Appalachian Prison Book Project

My knees gave way beneath me, rough brick scraping against my back as I fell to the sidewalk, shaking. My father’s words, staticized by the poor reception of our rural home, circled my head like relentless vultures. Your brother killed a man.

Tanner was arrested and charged with first-degree murder that same day. Already, his identity, and that of my family, was being morphed by a gossiping community, lies rooting like easy-spreading weeds that infiltrated and confused memories of the boy I grew up with. Rumors thrived. My nineteen-year-old brother became something of a local legend, always the monster.

In the months following, Tanner talked a lot about blankets. Blankets that were too short, too thin. Blankets that had too many holes, were too cold. He complained about meals that were too small and freedoms that were too shackled, and I, in my world of abundance, moved to Morgantown, West Virginia, to begin graduate study at the state university. Too many nights, I sat in my kitchen, crumbling under the guilt of my success, and then I found the Appalachian Prison Book Project (APBP).

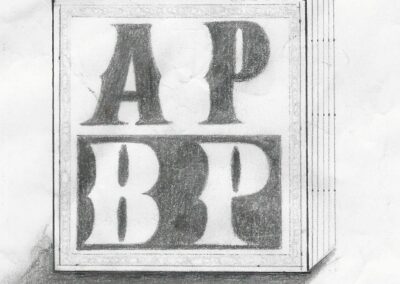

This nonprofit believes in education as a foundational right, advocating for a more restorative justice model, and fulfills this mission by answering book requests from incarcerated individuals. Founded in 2004, APBP has mailed more than 50,000 free books to people in prisons and jails across six Appalachian states. APBP also creates book clubs inside prisons, provides tuition support for people in prison taking West Virginia University classes, and offers education scholarships to recently released people enrolled in a West Virginia college or university. I found them at my worst, an older sister who had failed in guiding her brother to a decent existence, and they welcomed me.

The first book request I opened included a photo of a young man and his parents. He wanted to thank the organization for their service, sending a rare memento as payment.

I cradled this photo, wondering when, or if, I could forgive my brother without violating my morals. The proud eyes of the mother in the photo reminded me that no one hopes to raise a criminal. No child dreams of living behind bars. Quite the opposite, my brother wished for nothing more than to escape a longstanding family tradition of violence and addiction, but too often, playpens become prison cells.

Still holding this stranger’s family, I realized I could empathetically hold Tanner accountable. I could recognize his downfalls while continuing to love the kindness and ambition that is also part of who he is. APBP not only serves incarcerated individuals; they help outsiders come to terms with imprisonment, replacing ignorant stereotypes with the truth of human complexity, and build upon this empathy to encourage support for institutional change that is long overdue.

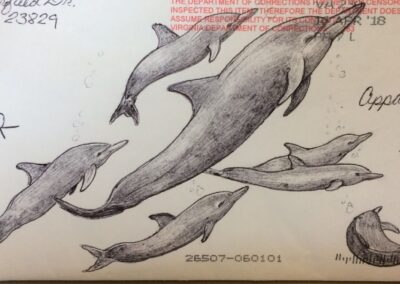

Still awaiting his trial, my brother calls to discuss Westerns and autobiographies that help him escape the long and solitary hours of maximum security or inspire him to adopt a kinder lifestyle. I trust Tanner’s future to the books he reads, and I hope those texts that I have chosen for the bookish individuals who write to APBP, including an unexpected amount of Westerns, will somehow touch their lives or simply help the hours pass.

Artwork

Destinee Harper is a poet, essayist, and flash fiction writer from Harrisonburg, Virginia. Currently, she works as a graduate instructor at West Virginia University as well as an assistant education coordinator for the Appalachian Prison Book Project. She believes in the restorative property of literature but now realizes, through the pandemic and hectic political climate, that living in a science fiction novel might not be as fun as she once thought.

For more information about the Appalachian Prison Book Project, visit

appalachianprisonbookproject.org