Okay, it’s only stuff I’ve written, but since I don’t have any extra hand sanitizer, toilet paper, or bonus Tiger King footage, this seemed like the most immediately positive gesture possible.

For the rest of the week, four Kindle versions of my books are FREE. To entice you (or scare you away), I’ll include a synopsis and sample, below.

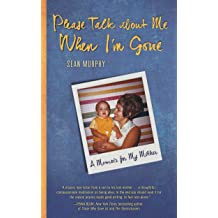

First up, my memoir, Please Talk about Me When I’m Gone, which I’d describe as an extended meditation on family, illness, grief, and recovery (for starters).

Synopsis:

Question: How do you get over it?

Answer: You don’t. You don’t want to. It makes you who you are.

Sean Murphy lost his mother days after her fifty-ninth birthday, following a five-year battle with cancer. In this eloquent memoir, he explores his family history through the context of grief, compassion, faith, and the cultivation of an artistic sensibility. Unfolding in a range of voices, brutal and tender in its portrayal of terminal illness, Please Talk about Me When I’m Gone is an unyielding love story, in which devotion and memory are capable of transcending death.

Sample:

How do you get over the loss?

That was the question I asked a former girlfriend who lost her father when she was a teenager. To cancer, of course. “You don’t,” she said. It’s just as awful as you’d imagine, she didn’t say. She didn’t have to, because you can’t imagine and you don’t want to imagine. How could you imagine? And, oddly enough, that succinct, painfully honest answer was more comforting than it sounded. In a way, when you think about it (does everyone think about it? Are some people able to avoid thinking about it?) there’s an unexpected salve in that sentiment: You don’t get over it. Or, by not getting over it, that’s how you survive it. It becomes part of you, and it is henceforth an inviolable aspect of your existence, like a chronic condition you inherit or develop along the way and manage as best you can.

Please talk about me when I’m gone. That’s the title of this memoir. It’s also the presumptive title of any memoir. More, it’s the unwritten title of any work of art—a desire to have those thoughts and feelings articulated, read, understood, appreciated. More still, it’s the often unexpressed message of any individual life: We want to be discussed, loved, and celebrated after we’re no longer around. Mostly we don’t want to be quickly or easily forgotten.

FREE Kindle version available here.

Next, a novel.

Synopsis:

Byron is a real piece of work in progress: old enough to own his own condo and pay all his bills most of the time; young enough to be unmarried but understand he is not getting any younger. Byron would love to mix things up and instigate some excitement into his own humble narrative. Unfortunately, a fight scene is not feasible, a car chase is getting too carried away, and a love interest appears to be out of the question. Also, he has to be awake and ready to work in the morning, just like everyone else. A recovering bartender, Byron struggled to escape the self-destructive restaurant business, but finds that the drinking and drugging of the corporate world are more pervasive—and encouraged—than he could ever have imagined. He finds himself unprepared for life after thirty, and ambivalent about the semi-fortune his stock options might eventually yield. Then, when a rumor circulates that a devastating round of layoffs is scheduled to occur just before Christmas, Byron begins to envision where he’ll be when something approximating reality comes crashing down. Not to Mention a Nice Life examines corporate America during the not-so-quiet storm that preceded the historic economic meltdown of 2008. A literary expansion on “Office Space,” this novel provides an answer to a question not enough people have asked: What happened to Holden Caulfield when he grew up? He got a job.

Sample:

I still have hangovers, thank God.

Everyone who has known an alcoholic knows that as soon as you stop feeling the pain, it’s because you are no longer feeling the pain; you are no longer feeling much of anything.

So, I welcome the horrors of the digital cock crowing in my ear at an uncalled for hour, am grateful for the flaming phlegm in my throat, the snakes chasing their tails through my sinuses, the smoke stuck behind my eyelids, the shards of glass in my gut, and the special ring of hell circling my head. Because if it weren’t for those handful of my least favorite things, I’d know I had some serious problems.

All of us can think of a friend whose father (or mother for that matter), we came to understand, was in an entirely different league when it came to the science of cirrhosis. The man who falls asleep fully clothed with a snifter balanced over his balls, then up and out the door before sunrise—like the rest of the inverted vampires who do their dirty work during the day in three piece suits. Maybe it was a martini at lunch, or several cigarettes an hour to take the edge off. Whatever it was, whatever it took, they always made it out, and they always came back, for the family and to the refrigerator, filled with the best friends anyone can afford.

Our friends’ fathers came of age in the bad old days that fight it out, for posterity, in the pages of books, uneasy memories and the wishful thinking of TV reruns: the ‘50’s. These are men who have never opened a bottle of wine and have no use for imported beer, men who actually have rye in their liquor cabinets—who still have liquor cabinets for that matter. These are men who were raised by men that never considered church or sick-days optional, and the only thing they disliked more than strangers was their neighbors. Men who didn’t believe in diseases and didn’t drink to escape so much as to remind themselves exactly what they never had a chance to become. Theirs was an alcoholism that did not involve happy hours and karaoke contests; theirs was a sit down with the radio and a whiskey sour, a refill with dinner and one before, during and after the ballgame. Or maybe they’d mow the lawn to liven things up, tinker under the hood of a car that had decades to go before it could become a classic. Or perhaps friends would come over to play cards. Sometimes a second bottle would get broken out. This was a slow burn of similar nights: stiff upper lips, the sun setting on boys playing baseball, mothers sitting on the couch watching TVs families did not yet own, of forced smiles battling bottled tears in the bottom of a coffee mug, of amphetamines and affairs, overhead fans and undernourished kids, of evening papers and a creeping conviction that there is no God, of poets unable to make art out of the mess they’d made of their lives.

It was a hard time where people did not live happily ever after, if they ever lived at all. It was a time, in other words, not unlike our own.

FREE Kindle version available, here.

Now, for some non-fiction. For the last 20 years, I’ve published a lot of essays covering everything from the technology industry to politics, movies, books, and especially music.

Synopsis:

In this collection of essays, reviews and ruminations, best-selling author Sean Murphy attempts to tackle the world in writing, one topic at a time. Selecting a sampling of his most popular pieces as well as some personal favorites, Murphy ranges from music to movies, literature to politics, sports to tributes for the departed. At his blog, Murphy’s Law, and as a columnist for PopMatters and contributing editor for The Weeklings, Murphy has combined enthusiasm and proficiency in the service of short and extended analyses. Throughout this compilation he shifts seamlessly between culture, the arts and an ongoing interrogation of American society.

Why is Robert Johnson the most influential American musician of the 20th Century? How—and why—did Dennis Miller go from being one of the better comedians in the world to a humorless hack? Why are even the most gifted novelists unable to write convincing sex scenes in their fiction? Was the first round of Hagler vs. Hearns in 1985 the most exciting three minutes in sporting history? Is it reasonable to suggest that Chinatown is the only perfect American film ever made? What does it mean to declare Stephen King the Paul Bunyan of letters? Is it possible we don’t adequately celebrate either Moby Dick or The Great Gatsby? Does nostalgia play a defensible, even necessary role in one’s art or life?

By turns studious, confrontational, hilarious and philosophical, Murphy’s Law, Vol. One will leave readers better informed, provoked and, hopefully, inspired to discover the work of some geniuses who’ve fallen outside the lower frequencies.

Samples:

a. I’m not certain if it has anything to do with what you study in college, or the type of person you already are (of course the two are not mutually exclusive by any means) but speaking for myself, I suspect that if you are a certain age and not already convinced that God is White and the GOP is Right (and anyone under the age of twenty-one who is certain of either of those things is already a lost cause, intellectually and morally), reading a book like The Road To Wigan Pier changes you. Reading a book like The Jungle changes you. Books like Madame Bovary change you. Books like The Second Sex change you. Books like Notes From Underground change you. Books like Invisible Man change you. Then you might start reading poetry and come to appreciate what William Carlos Williams meant when he wrote “It is difficult to get the news from poems, yet men die miserably every day for lack of what is found there.” These works alter your perception of the big picture: cause and effect, agency vs. incapacity and history vs. ideology and the myriad ways Truth and History are manufactured by the so-called winners.

b. It’s possible, if not probable that our technological toys have provided us with everything but perspective, making us increasingly oblivious to the realities of people we’re not familiar with. This might help explain a country, like ours, with unlimited access to all sorts of content being as polarized (politically, psychologically, personally) as any time in recent memory. And undoubtedly the anonymity — and security — of electronic interaction makes us more immune to/intolerant of opinions we don’t share.

c. I love the ’60s and write often about the significant things that did happen, did not happen and should have happened during that decade. In terms of import — be it artistic, social, political, cultural — opinions on what matters and endures about the ’60s often says as much or more about the person offering an opinion. In spite of my interest and enthusiasm, I’m pretty sure I wouldn’t have wanted to be a young man in the ’60s. Sure, I could have been witness to too many milestones to count, in real time. I also could have been killed in Vietnam, or in the streets, or fried my greedy brain with too much LSD or, worst of all, somehow been a Nixon supporter. Every event and individual from this seminal decade has assumed mythic status, but so many of the figures we admire were not admirable people. It’s worth the gifts they left, we say, often correctly. But has there been a single period in American history where so many people get too much credit for talking loudly and saying little? The older I get and the more I learn — about the ’60s, America, myself — the deeper my awe of the man who changed his name to Muhammad Ali grows.

FREE Kindle version available, here.

More opinions, shout-outs, and deep dives into the shallow depths of society (or something).

Synopsis:

Selecting a sampling of his most popular pieces as well as some personal favorites, Murphy ranges from movies and literature to politics, sports and tributes for the departed. At his blog, Murphy’s Law, and as a columnist for PopMatters and contributing editor for The Weeklings, Murphy has combined enthusiasm and proficiency in the service of short and extended analyses. Throughout this compilation he shifts seamlessly between culture, the arts and an ongoing interrogation of American society.

Ranging from acclaimed foreign films like Walkabout to addictive pop-candy like Caddyshack, or remembering the impact of Steve Jobs and Norio Ohga (who invented the compact disc), this collection at times eulogizes, castigates and celebrates culture, both high and lowbrow. Whether describing the ordeal of putting down a beloved dog, the melodrama of unrequited teen crushes, or seeking out authentic Chinese cuisine in rural Virginia, Murphy takes a deep dive on topics familiar and obscure. Were the ‘90s a soulless wasteland or an artistic apogee, ripe for reassessment? What’s the best scene in cinematic history? How did Muhammad Ali’s most important fight take place outside the ring? Did mistakes made early in Obama’s first term presage the unimaginable spectacle of Donald Trump? Can the millennial generation understand, much less appreciate, the lost art of making mix-tapes? Has 21st Century information overload made enlightenment possible, or even desirable?

Samples:

a. I’m always on guard against two things above all: cliché and nostalgia, as both are traps that short-circuit critical thought and unfettered perspective. But damn if I don’t miss reading books. Don’t get me wrong: I still read books, all the time. But it’s been over a decade since I spent several hours, uninterrupted, mug nuzzled in a paperback. Much as I like to resist them, the shrieks from my devices, arrayed around me like so many electronic magpies, are all but impossible to ignore. I blame myself for this lack of discipline, but I reminisce about a time when it was novel to walk into the other room once or twice an hour to check email, and then return to my novel. Now, I can hardly watch a movie or read an essay (much less a book) without constantly making sure I’m not missing anything. In my paltry defense I’d say it’s less the FOMO phenomenon and more an actual rewiring of the way my mind works. That scares the shit out of me, especially as someone with artistic inclinations. Even at work, it’s not uncommon for me to have multiple windows open at any given time, along with Outlook, a spreadsheet or two and one or two documents, perhaps with music playing, and I’ll open a new window and while I’m waiting for it to load (three seconds being an eternity; an actual connection issue an affront), I’ll check my mail, and then go back to the fresh window and forget what I opened it for. This too mortifies me. I’m as much a tech junkie as anyone, and while I’d like to blame these portable, connected toys for corrupting our supposedly more serene lives, I suspect it’s even worse: technology has tricked us into being busier every single day, and it’s not even work, it’s play. Is this a trend we can slow down? Should we? Or are we advancing our evolution, fast-tracking an ability to connect, communicate and yes, commiserate, in a fashion previously unimagined? Having virtually everything that has been or is being created, available for free, in real time, is something I would have considered an outright miracle as a bored young punk; now it increasingly seems like the gift that will keep taking.

b. You can always tell when a dog is unhappy because the rest of the time they are either ecstatic or asleep. A common misconception is that, as dog lovers, we crave subservience, and it feeds our insatiable egos. That’s not why people have dogs, it’s why people have children (just kidding). In truth, it’s a great deal more complicated, more philosophical than that. Sure, what’s not to love about an incorruptibly honest, obedient, affirmative presence one can count on every second of every day?

And yet, I suspect, if you spoke with people who are not just dog people, but those people—the type who not only talk incessantly about their own dogs, but other dogs, and are up for talking about dogs, and meeting new dogs, even if it occasionally involves stalking an unsuspecting owner on the trail or outside a supermarket, because it’s not only bad form, but impossible to not make the attempt—they’d suggest that the secret ingredient of our obsession is at once selfish and something more than a little noble, in an aspirational sense: dogs, with their total lack of guile and excess of fidelity, are ceaselessly humbling, and remind us of what’s so lacking in our fellow humans, and within ourselves.

c. You can, of course, approximate the experience via iPod and playlists. Anyone can do that. And that’s the problem: anyone can do it. It’s too easy. It might even be easier to create superior product, because when the entire world is your library (also called iTunes), there are no limitations a quick download can’t conquer. But a mixed tape, aside from being an art unto itself (which songs would, assembled in the appropriate order, come as close as humanly possible to 45 minutes per side, often requiring a calculator and album credits to ensure individual song lengths), demanded effort and considerable deliberation, all based on songs already available to the mix-maker. Thus, it was truly a reflection of one’s personality; these were songs the individual had cared about enough to own the album (or, ahem, the CD) in the first place.

Not to get all Ray Davies or anything, but the old ways ain’t ever coming back. So it’s seems respectful and perhaps more than a little necessary to let out a little howl for the way we used to roll. What we’re left with now when it comes to mixmanship is, by default, an exercise in onanism: we make playlists for ourselves. The sound quality and song selection are unquestionably superior, but the impetus for creativity and the urgency of the interaction is lacking. A playlist listened to with headphones on the morning commute can never compare with the indelible memories an effective mixed tape could inspire. It was always a fundamentally human exchange: it was an unspoken act of love. Giving was often as good as receiving. There was a specific message that only a mixed tape was capable of conveying, and once we lost that, we all lost a small but irretrievable portion of our souls.

FREE Kindle version available, here.

Bonus footage of the author reading (in Brooklyn!), below.