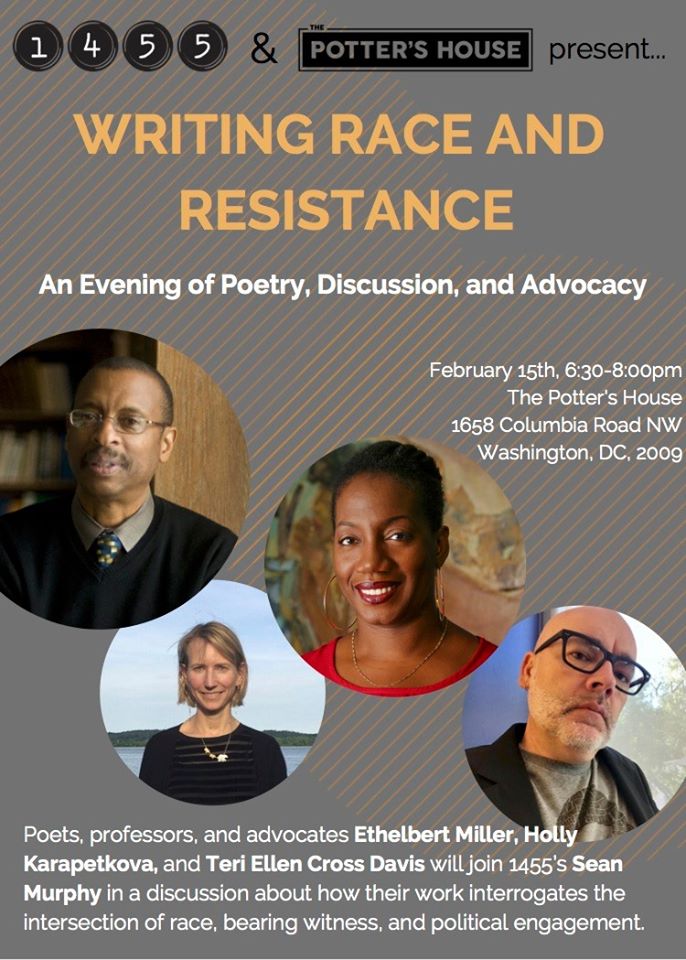

1455 is pleased and proud to partner with the historic Potter’s House, in D.C. (More about them and their mission, here.)

For our first collaboration, and to celebrate Black History Month, the topic was “Writing Race and Resistance.” 1455 was honored to include three brilliant writers (and friends), bios below.

Eugene Ethelbert Miller, best known as E. Ethelbert Miller, is an African-American poet, teacher and literary activist, based in Washington, DC. He is the author of several collections of poetry and two memoirs, the editor of Poet Lore magazine, and the host of the weekly WPFW morning radio show On the Margin.

Holly Karapetkova’s poetry, prose, and translations have appeared widely in print and online, and she’s the author of Words We Might One Day Say, winner of the 2010 Washington Writers’ Publishing House Poetry Award, and Towline, winner of the 2016 Vern Rutsala Poetry Contest from Cloudbank Books. Her current manuscript projects, Still Life With White and Planter’s Wife grapple with the deep wounds left by our history of racism, slavery, and environmental destruction. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing and teaches at Marymount University.

Teri Ellen Cross Davis is the author of Haint, (Gival Press) winner of the 2017 Ohioana Book Award for Poetry. She has received fellowships to attend Cave Canem, the Virginia Center for Creative Arts, Hedgebrook, the Community of Writers Workshop, and the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown. She is the 2019/20 HoCoPoLitSo Writer-in-Residence, adjunct professor at George Washington University, and the poetry coordinator for the Folger Shakespeare Library.

From 1455 Executive Director Sean Murphy’s opening remarks:

When I first met Leigh and her team here at Potter’s House, we agreed that, given the historic and cultural import of this remarkable venue, it made sense to plan our first event during February to celebrate Black History Month. Aside from my role of founder and Executive Director of a non-profit writers organization that seeks to celebrate creativity and build community, I also am a writer. And much of my poetry and musical criticism concerns itself with one my largest passions: jazz music, which is, alongside the blues, America’s signal artistic invention, yet both have very deep roots in African history and tradition. How I came to be a white man writing about obscure jazz musicians is really part and parcel to how I came to be a white man listening to jazz, and blues. But, and I suspect this will be a recurring theme tonight, it is, as they say, complicated. If you approach art and life from the perspective of seeing all experience as the proverbial melting pot, there are, or should be, no boundaries. But that’s easier said than done, as history shows us.

Video from the event, below, and our thanks to Ken Mutamba from Gold Hat Media Group, LLC.

The living owe it to those who no longer can speak to tell their story for them.

Czeslaw Milosz, one of the great artists of the last century, was both a poet and a professor. He could appreciate literature from both angles: the creation of it as a writer and the appreciation of it as a reader. Having seen some of the atrocity humankind was capable of during his lifetime, his work uses words to elegize, accuse and above all, to remember. His great obsession was doing his part to ensure that the suffering and the bravery and the cruelty were a little less possible to ignore and forget.

Milan Kundera, in the book Testaments Betrayed, explains his vision of the wrter’s acumen, which is “a considered, stubborn, furious nonidentification, conceived not as evasion or passivity but as resistance, defiance, rebellion.” For a white writer tackling topics ostensibly outside their strict area of experience, I have always found this a liberating proposition. So for me, this poetry is obviously a form of creative and artistic expression, but it’s also—crucially—an act of bearing witness; a defiance against forgetting, a refusal to not acknowledge and celebrate our collective heritage, as human beings.