Winston Churchill famously remarked: “My vices protect me but they would assassinate you.”

And he managed to achieve a thing or two in his time, decadent proclivities be damned. But his boast, equally self-aware and arrogant, invariably invokes the myriad stories of debauchery amongst rock music gods and lesser opportunists, and one thinks: how have more of them not died? Who could keep up that pace, the commitment, the insanity of repetition with guaranteed, diminished returns, etc.?

“It’s better to burn out than fade away,” Neil Young famously—if facetiously—sang. Years before that, he also opined “some get stoned, some get strange, but sooner or later it all gets real.” Put another way, and as sardonically as possible: there’s only one Keith Richards.

But what about, for a change of pace, assessing an artist’s virtues?

Is there anything at once more inspiring and daunting than reading about high-functioning types and the routines they’ve adapted in order to achieve what they did—and do?

Just as it’s the drink, drug, and ability to forsake sleep that separates our vitiated legends from the legion of pretenders and copycats, it’s the habits and compulsions of the best artists that leave one staggered, even intimidated. Similar questions abound: who can do this? How do they do it?

And the answer is: because they can. Because they must.

Like every other writer, I’ve read more than my fair share of books about writing and writers. And, naturally, I can never get enough. There’s something about their combination of insight and solidarity, mixed with object lessons found in even the substandard offerings; nuggets of gold amongst the platitudes and clichés; reminders that each writer must confront a personal gauntlet of unremitting rejection en route to something we might consider success (and that’s just the relative percentage who persevere after a series of setbacks that would make Sir Ernest Shackleton crawl under an iceberg). In the final analysis, these thrice-told tales testify more to perseverance than the black hole of desolation. And, not least, there’s the oddly comforting fact that no two writing careers are identical, yet there are common themes that emerge, crossing generations and languages and the inexplicable trends that reward hacks and doom geniuses to obscurity. Et cetera.

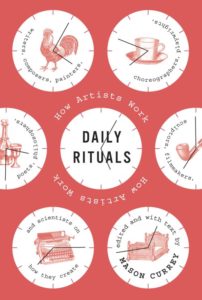

It was, then, with hope and expectation that I cracked open the latest such book, Mason Currey’s Daily Rituals: How Artists Work, which takes actual habits and routines from famous artists and scientists, as documented in their own words and correspondence. I recommend it without reservation to anyone, and the reader need not be a writer or even have an ounce of creativity to appreciate—and learn from—the mostly positive, if imposing collection of insights.

I’ll say, as someone who has been writing (with varying degrees of succession and consistency) over more than two decades, there’s literally something in every one of these quotes that I can identify with, understand, or seek to emulate. I also know this type of dedication, discipline, and focus is not limited to artists; mastery involves an almost impossible combination of obsession, passion, respect (for the subject; for the self), ambition, and not lastly, balance. As such, I’m certain virtually anyone will find much to savor here.

For all you TL;DR types, there are indeed a handful of traits/themes that recur and it’s not a generalization to say that pretty much every one of these testimonials (with notable exceptions) incorporates some/all of the following guidelines:

- Up early

- Daily walks

- Daily quota of words/pages written (or hours spent)

- Minimal distractions, whenever possible

- Non-existent social life

- Extreme moderation with alcohol (made up for in many cases with coffee and/or cigarettes)

So here we go. And, of course, any comments or recommendations are invited. What books have proved valuable to your own endeavors? Are there other quotes or admonitions from famous (or infamous) folks you find inspiring? And not least, what are some of your personal practices, routines, or obsessions that stimulate a more productive writing life? What has worked for you? What hasn’t?

“Sooner or later, the great men turn out to be all alike. They never stop working. They never lose a minute. It is very depressing.”

–V.S. Pritchett

“Time is short, my strength is limited, the office is a horror, the apartment is noisy, and if a pleasant, straightforward life is not possible then one must try to wriggle through by subtle maneuvers.”

–Franz Kafka

Beethoven’s breakfast was coffee, which he prepared himself with great care—he determined that there should be sixty beans per cup, and he often counted them out one by one for a precise dose.

–Ludwig van Beethoven

“All those I think who have lived as literary men—working daily as literary labourers—will agree with me that three hours a day will produce as much as a man ought to write. But then, he should have so trained himself that he shall be able to work continuously during those three hours.”

–Anthony Trollope

“The repetition itself becomes the important thing; it’s a form of mesmerism. I mesmerize myself to reach a deeper state of mind…(and) physical strength is as necessary as artistic sensitivity.” (He discovered that the sedentary lifestyle caused him to gain weight rapidly…he soon resolved to change his habits completely, moving with his wife to a rural area, quitting smoking, drinking less, and eating a diet of mostly vegetables and fish. He also started running daily. The one drawback to this self-made schedule, Murakami admitted in a 2008 essay, is that it doesn’t allow for much of a social life…but he decided that the indispensable relationship in his life was with his readers. “My readers would welcome whatever lifestyle I chose, as long as I made sure each new work was an improvement over the last. And shouldn’t that be my duty—my top priority—as a novelist?”

–Haruki Murakami

“I am not able to write regularly…but the important thing is that I don’t do anything else. I avoid the social life normally associated with publishing. I don’t go to cocktail parties, I don’t give or go to dinner parties. I need that time in the evening because I can do a tremendous amount of work then. And I can concentrate. When I sit down to write I never brood.”

–Toni Morrison

(Despite boasting otherwise) the great British diarist and biographer often had a terrible time getting out of bed in the morning and frequently fell prey to the “vile habit of wasting the precious morning hours in lazy slumber.”

–James Boswell

Amis said that he writes every weekday, driving himself to an office less than a mile from his London apartment. “Everyone assumes I’m a systematic and nose-to-the-grindstone kind of person…but to me it seems like a part-time job, really, in that writing from eleven to one continuously is a very good day’s work. Then you can read or play tennis or snooker. Two hours. I think most writers would be very happy with two hours of concentrated work.”

–Martin Amis

“To me George was a little sad all the time because he had this compulsion to work,” Ira Gershwin said of his brother. He was dismissive of inspiration, saying that if he waited for the muse he would compose at most three songs a year. It was better to work every day. “Like the pugilist, the songwriter must always keep in training.”

–George Gershwin

Heller wrote Catch-22 in the evenings after work, sitting at the kitchen table in his Manhattan apartment. “I spent two or three hours a night on it for eight years. I gave up once and started watching television with my wife. Television drove me back to Catch-22. I couldn’t imagine what Americans did at night when they weren’t writing novels.”

–Joseph Heller

His contemporaries remember him as having a cheerful disposition, but Liszt obviously had his share of demons. A younger colleague once asked why he didn’t keep a diary. “To live one’s life is hard enough. Why write down all the misery? It would resemble nothing more than the inventory of a torture chamber.”

–Franz Liszt

“I must write each day without fail, not so much for the success of the work, as in order not to get out of my routine.”

–Leo Tolstoy

“The seed of a future composition usually reveals itself suddenly, in the most unexpected fashion. If the soil is favourable, that is, if I am in the mood for work, this seed takes root with inconceivable strength and speed, bursts through the soil, puts out roots, leaves, twigs, and finally flowers: I cannot define the creative process except through this metaphor…it would be futile for me to try and express to you in words the boundless bliss of that feeling which envelops you when it begins to take definite forms. You forget everything, you are almost insane, everything inside you trembles and writhes, you scarcely manage to set down sketches, one idea presses upon another.”

–Pytor Ilich Tchaikovsky

When in the throes of a new idea, he pleaded with his wife to let him be free of family obligations; sometimes, in these states, he would work for up to twenty-two hours straight without sleep. (His wife) eventually accepted his relentless focus on his work, but not without some resentment. She wrote to him in 1888, “I wonder do you think of me in the midst of that work of yours of which I am so proud and yet so jealous, for I know it has stolen from me part of my husband’s heart, for where his thoughts and interests lie, there must his heart be.”

–Alexander Graham Bell

When in the grip of creative inspiration, he painted nonstop, “in a dumb fury of work.”

–Vincent van Gogh

Shortly after graduation from college, Franzen married his girlfriend, also an aspiring novelist, and the pair settled down to work in classic starving-artist fashion. They found an apartment outside Boston for $300 a month, stocked up on ten-pound bags of rice and enormous packages of frozen chicken, and allowed themselves to eat out only once a year, on their anniversary…five days a week, the couple wrote for eight hours a day, ate dinner, and then read for four or five more hours. “I was frantically driven,” Franzen said. “I got up after breakfast, sat down at the desk and worked till dark, basically.”

To force himself to concentrate on his 2001 novel, The Corrections, he would seal himself in his Harlem studio with the blinds drawn and the lights off, sitting before the computer keyboard wearing earplugs, earmuffs, and a blindfold. It still took him four years, and thousands of discarded pages, to complete the book. “I was in such a harmful pattern. In a way, it would begin on a Friday, when I would realize what I’d been working on all week was bad…between five and six, I’d get drunk on vodka—shot glasses. Then have dinner, much too late, consumed with a sick sense of failure. I hated myself the entire time.”

–Jonathan Franzen

“I work all the time…I work every day. I work weekends, I work nights…some people looking at that from the outside might use that modern term “workaholic,” or might see this as obsessive or destructive. But it’s not work to me, it’s just what I do, that’s my life. I also spend a lot of time with my family, and I sing, and go to ball games…I don’t have a one-dimensional life. But I basically do work all the time. I don’t watch television. But it’s not work, it’s not work, it’s my life. It’s what I do. It’s what I like to do…you have to have high levels of bodily energy and not everybody has it. I’m not physically strong, but I have very great intellectual energy, I always have…I can literally sit and work all day once I get going, not everybody can do that. It’s not a moral issue. Some people seem to see that as a moral question. It isn’t. It’s a question of body type and temperament and energy levels. I don’t know what makes us what we are.”

–Stephen Jay Gould

“Discipline is an ideal for the self. If you have to discipline yourself to achieve art, you discipline yourself. There’s no one way—there’s too much drivel about this subject. You’re who you are, not Fitzgerald or Thomas Wolfe. You write by sitting down and writing. There’s no particular time or place—you suit yourself, your nature. How one works, assuming he’s disciplined, doesn’t matter. If he or she is not disciplined, no sympathetic magic will help. The trick is to make time—not steal it—and produce the fiction. If the stories come, you get them written, you’re on the right track. Eventually everyone learns his or her own best way. The real mystery to crack is you.”

–Bernard Malamud

Remember: Sooner or later, it all gets real.

Let us know what you think! And, you can help VCLA in so many ways: like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter and Instagram, sign up for our newsletter, spread the good word, make a donation and tell every single person you’ve ever met in your life!

*Amazing images courtesy of Horse and Hare Hand Carved Art + Design.